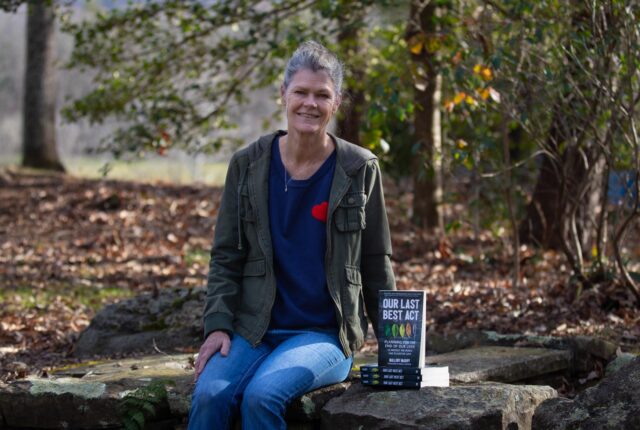

After her parents’ sudden deaths, Dr. Mallory McDuff took a one-year journey to revise her final wishes with climate change and community in mind. What she discovered about sustainable end-of-life practices changed not only her death plans, but also her life and her wider community.

By Mallory McDuff, Ph.D., Director of Environmental Education and Professor of Environmental Studies and Outdoor Leadership

This story was originally published in the 2022 Owl & Spade Magazine